Sajan Sankaran is an engineer who looks at music (more specifically Dhrupad) and yoga through a very clear lens. In one of his articles, he writes how desi and margi forms of music were explained by his guru late Shri Ramakanth Gundecha, who said that the purpose of the music, as well as the intention and perspective of the practitioner defines music.

At a session at his Dhrupad Gurukula, Ramakant ji had said one kind of music can communicate at a level where other mediums cannot express emotion adequately. “Such music – that takes one towards ‘thoughtfullness’ is desi music.” Mārgi music on the other hand, “is that which takes one towards ‘thoughtlessness’. Towards stillness. Silence.” (Mārgi and Desi Music. In traditional Indian arts, we… | by Sajan Sankaran | Medium

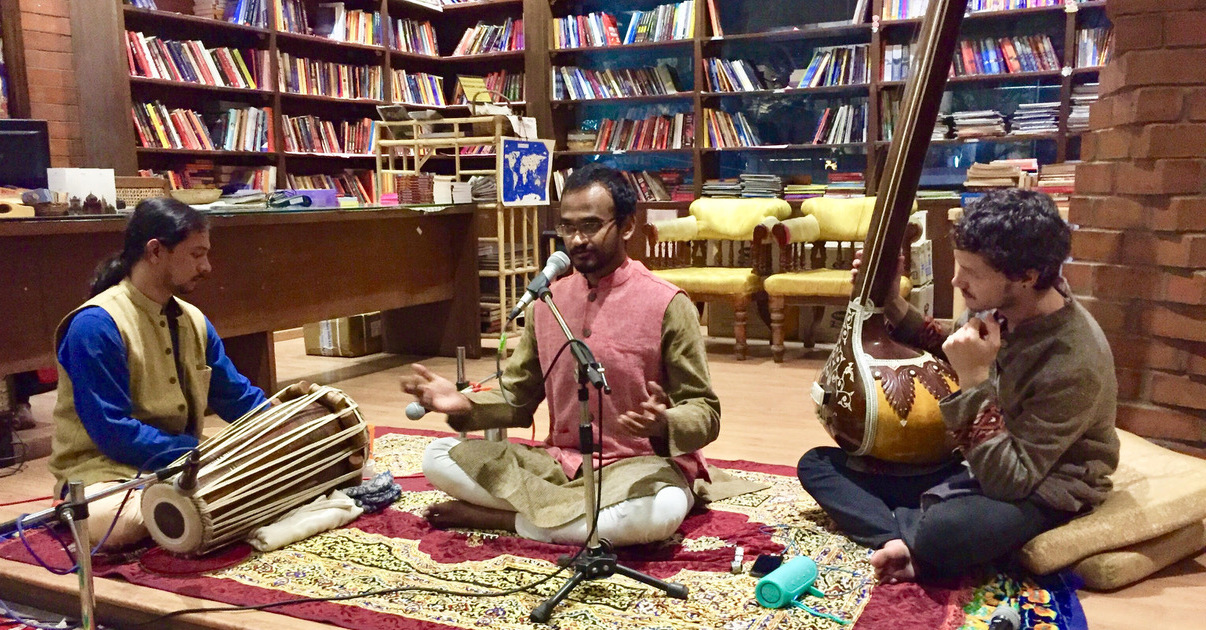

In his sessions for Indica Courses, Sajan is focussing on beginner level courses, “in the sense that prior Dhrupad training is not a prerequisite to attend. I hope once the learner base grows large enough, we can move on to more detailed and advanced courses. I try to accommodate people with all backgrounds of musical training and exposure to the best of my ability in the program design.”

One Dhrupad observer has said: through music, we are willing to approach cultures beyond our own, and that on our shelves (and in our ears), we place them into conversation with each other.”

How can Dhrupad speak to other music cultures? How have you witnessed it in your travels? How do the tones, rhythms, and melodies of Indian music help to create empathy between cultures?

I think Dhrupad deals with music at such an elemental level, and that makes it easy to relate to for any seeking mind. Dhrupad is said to be an exploration of pure sound. A large part of the rendition does not even have words, but just abstract syllables that carry the sound. The first principles of musical sound are by definition universal. The aesthetic of Dhrupad features a paced out, systematic unfolding of the various melodic and temporal entities. This naturally increases the conscious engagement with frameworks that are closer to first principles than most other musical systems, thus making its appeal fairly universal. Seeing the diverse geographic and cultural backgrounds of the various students at my Gurukul, and also seeing the reception to Dhrupad in my own travels in and out of India, has only reinforced this notion.

You are a prime example of Indian music taking several births to learn. An IIT graduate, what made you suddenly turn to Dhrupad. Did you recognize it as some past connection?

I certainly subscribe to the premise of continuity of knowledge across births. Given that I have no convincing way to look back though, I find more utility in being grateful for having arrived here, however it may have happened. When encountered with the vastness of this knowledge system and the growing but minuscule range of my own discovery of it, I find some respite in reminding myself that my sadhana now will manifest in some form in the next cycle!

The music is arranged into 6 primary ragas, 10 basic thats, Raginis and so on all bearing a relationship to our Gods. Can we then speak of this music as devotional in its aesthetic or as being drenched in Bhakti rasa?

It’s crucial to understand that Dhrupad, like many traditional Indian art forms, exists as an integral part of a larger whole. This art form embodies a conscious and unconscious blending of values from various domains of Indian knowledge systems, including different traditions of worship, as well as intellectual and philosophical traditions. Dhrupad seamlessly coexists with these multifaceted aspects of Indian culture. Even my personal exploration centers on investigating the convergence of Dhrupad and Yoga, both in philosophy and practice. It’s important to recognize that Dhrupad thus can’t be purely termed ‘secular’, in that it cannot be removed from its associations with multiple coexisting traditions. Many Dhrupad compositions have a devotional nature, reflecting their deep spiritual connections.

The approach to Dhrupad can vary, encompassing an intellectual and philosophical practice that worships the pure consonance of sound, or it can be explicitly devotional, involving visualizations and engagement with various forms. While the direction of worship need not be constrained by religion or form, the phenomenon itself is pervasive, transcending boundaries.

How important is it to know the history of Dhrupad to understand its current essence….its Vedic roots, the role of the Dagar family, your own gurus….is it an unbroken tradition. How important is it for learners to be aware of art history in music?

I think it’s very crucial. My Guru – late Pt. Ramakant Gundecha, spoke of two distinct functions of music. The communicative/ evocative, and the meditative/ that which stills the fluttering of the mind. While neither is superior or inferior, they both are distinct from each other. Yet, they’re very close to each other. With the additional layer of aesthetics and beauty, it becomes a delicate balancing act to retain conscious awareness of the purpose of the music.

We often hear that Indian music is not just for entertainment, but serves a higher goal. Losing the connection with the history and roots could end up making this an empty statement. It becomes essential to remind ourselves of the fundamental thought and philosophy that led to the development of the music. The history, despite appearing as plain information, helps retain conscious awareness of the underlying thought frameworks, that is crucial to both preserving, and developing the art form holistically.

What about the philosophy of Dhrupad? Can we say its meditative nature arises not just from its vocabulary but also from the way the masters wanted it to be a route to a higher consciousness?

I’d like to answer this question with a personal anecdote. I once had a fairly intense 40 minute class with my Guru, where he essentially taught me to sing just one note. The intensity of focus demanded and the level of detailing were both enormous. Only towards the end of the class, I was able to reach where he was trying to take me. With a satisfied expression, he turned off the tānpura and asked me, “why is this the ‘re’ of Bhoopali?”. After giving all the answers about consonance of the sound, and the internal relationality of the notes in the context of the rāga, I realised he was waiting to point at something else; especially when he asked me, “All that is okay. But why does this ‘re’ exist for Bhoopali?” I was flabbergasted, and just waited intently for him to reveal the answer. He said, “This ‘r’ exists just to give you an opportunity to take your mind to the state of refinement and focus that was needed to reach there”.

That one statement stayed with me, and clarified the true essential purpose of Dhrupad for me. The unique, paced out, detailed and meditative approach of Dhrupad suddenly made so much sense apart from the context of its subjective aesthetic beauty. This incident was monumental in cementing my already strong love for this tradition.

I’ve realised very frequently in class, that through the nāda I was producing, it was essentially the state of my mind that was being evaluated. Refined and elevated. The ‘music’ simply gives a very effective means of subtle communication between the guru and the shishya to engage in such a knowledge transmission.

You combine music and yoga in your life. How do you think Yoga practitioners would be aided by learning Dhrupad?

Music is usually seen by yoga practitioners as a tool to enhance the experience of other practices which are considered yoga. Like a flute playing in the background while practicing asanas, etc. By virtue of its general aesthetic and practice philosophy, Dhrupad allows one to look at the process of singing itself as yoga in practice. This can expand the horizons of the practitioner.

Being a distinct musical system that has developed over many centuries, Dhrupad also allows the practitioner to immerse into the phenomenon of aesthetics and beauty, which only enriches the experience of life itself.

While yoga is becoming popular around the world, people mostly still recognise it as a body practice. Engaging with a practice like Dhrupad can open one’s mind to a more holistic understanding of the system.

Is the general public aware of Gharanas or Sampradayas? Do you teach from your own learning, or is there a general base imparted?

To some extent, yes. Of course, Dhrupad in general faded out of the public consciousness, and is only now going through a revival since the past few decades. The general awareness about Dhrupad is quite lacking, but it’s fast growing.

There certainly is a general base of knowledge that gets transmitted. Every Guru does customise the pedagogy to varying extents too. The tradition is a living one, and as long as the continuity is maintained, innovation is encouraged. My Gurus worked a lot to make the teaching more structured and university accessible, and I do my best to uphold those principles in my own teaching. While I do customize, my teaching design a lot based on the need, I do not deviate from the core principles and philosophy of my Gurus’ teaching methods.

Do you think the digitization of music has impacted the tradition? Would the Dagars have imagined how music is being received today?

I think the impact has been huge. In the context of archiving and access, it’s only positive. Access to quality music has been democratised. Anybody from anywhere can today discover and experience the beauty of various musical traditions, and even learn it seriously.

I don’t think anybody could have imagined that we would get to where we are. I also feel that the response to the current scenario would vary greatly from individual to individual. I’m sure some people would be thrilled to see the possibilities, while others would lament at the same things.